An explanation of each step from planting the seeds to weaving the cloth is laid out, along with a short story that allows the reader to experience the Neolithic world through the eyes of the people performing the tasks. They speak a recreated (imagined) Neolithic language. The scenes occur in Neolithic Germany near the Rhine River, circa 5500BCE.

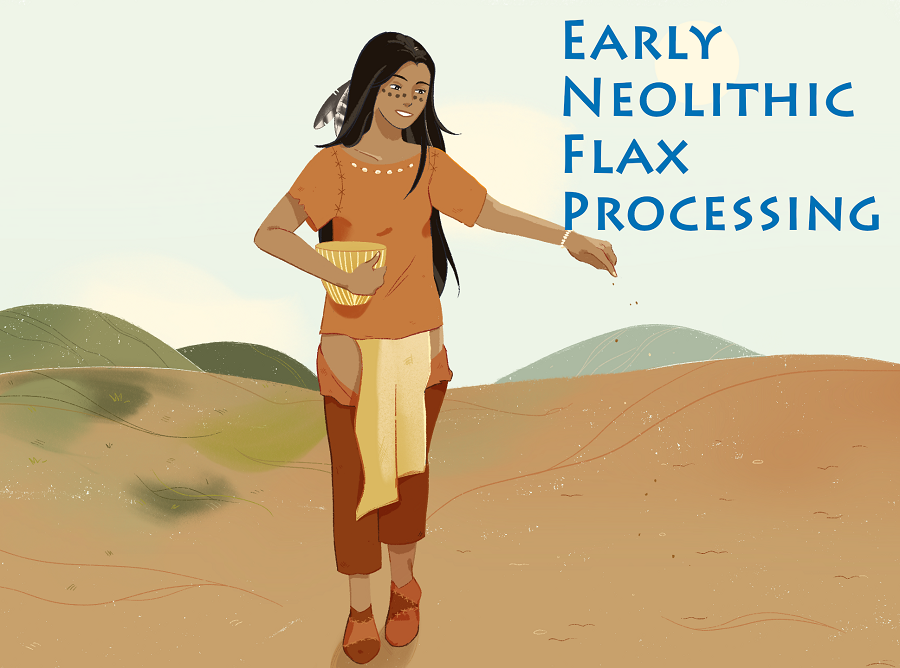

Sowing / Growing – Flax should be planted in well-drained soil with plenty of sunlight. While flax can survive clay-rich soil, it prefers average quality soil. The seeds would be hand-cast by workers, probably in a haphazard manner. Plants grown closely together make better flax to work with, growing more straight as they support each other and choke out the weeds. Planted in the earliest spring, just after the ground thaws (date of planting varies by location), the flax will grow over the next 100 or so days.

Aneha stood on the cold dirt, thankful she had worn her leather shoes, taking a quick break. She wore deer leather leggings and loincloth supported by a two-ply braided flax cord and a long leather shirt. However, she might remove it when it became warmer during the midday. She held a small clay fish her uncle had made full of flax seeds from last year's harvest in her hands.

Resuming her work, she stepped forward with a handful of seeds, carefully releasing only a small number of them at a time in a sideways scattering pattern, left to right. Scattering the seeds widely made work easier and used fewer seeds. Keeping them tightly packed would cause the plants to grow less broadly, producing better fibers. Farming was as much of an art form is a technical application of skill, as far as she was concerned.

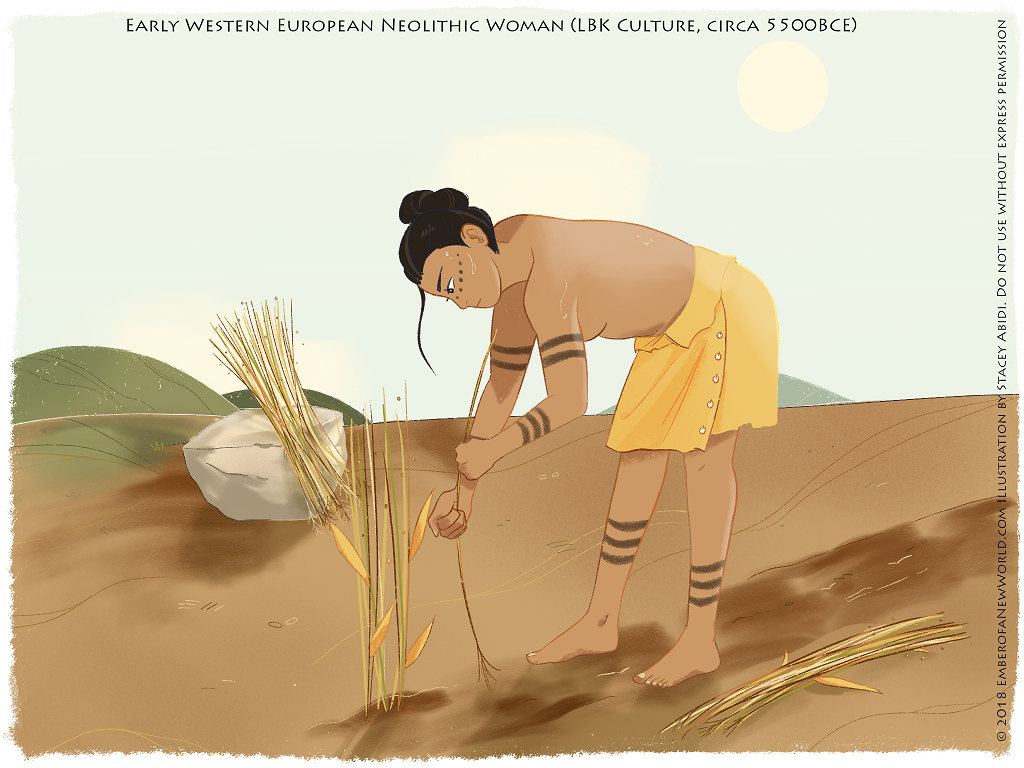

Harvesting – Flax is harvested roughly 100 days after planting when yellowing of the upper leaves and pods can be seen. By the point, the seed pods should be dry and ready to release their seeds, and flowers should all be gone. Workers pull the flax from the ground, holding the base of the plant. Flax is never cut but always pulled. The plants can be bundled, a single plant used to bound them into a “stook.” Flax would be left for a few days to dry in the sun.

"Eleh Aneha! Ehsu'eleh de tuh!" Malik exclaimed as he stepped into the flax field a little over 90 days since planting. His breechcloth chafed his skin in the heat of the mid-warm season, but a cool morning breeze helped a little. Before him, Aneha and three other women danced in the center of the field wearing summer wheat stalk wreaths. They were painted from head to toe in red ocher with black ash painted lines down their bodies, while two men beat drums singing the proper rituals to ensure a good harvest. Aneha paused her dance just long enough to consider the compliment, and smiled.

Ten days later, Malik bent forward, grasping a flax plant where it entered the dirt with his left hand, holding the plant's upper portion with his right hand. Using a firm but gentle tug, he removed the plant from the ground and tossed it into the pile before him. His back hurt from bending over, but he knew the soft feel of his linen cloak this past cold season had come from the cloth woven from the same sort work he did now. He could almost taste the coriander seasoning his people would trade flax and linen to obtain, as well as other goods. With luck, after their harvest, a trader would come by bringing shells, spices, and other delights. Above all, he hoped Aneha appreciated his compliment and remembered that he had said it.

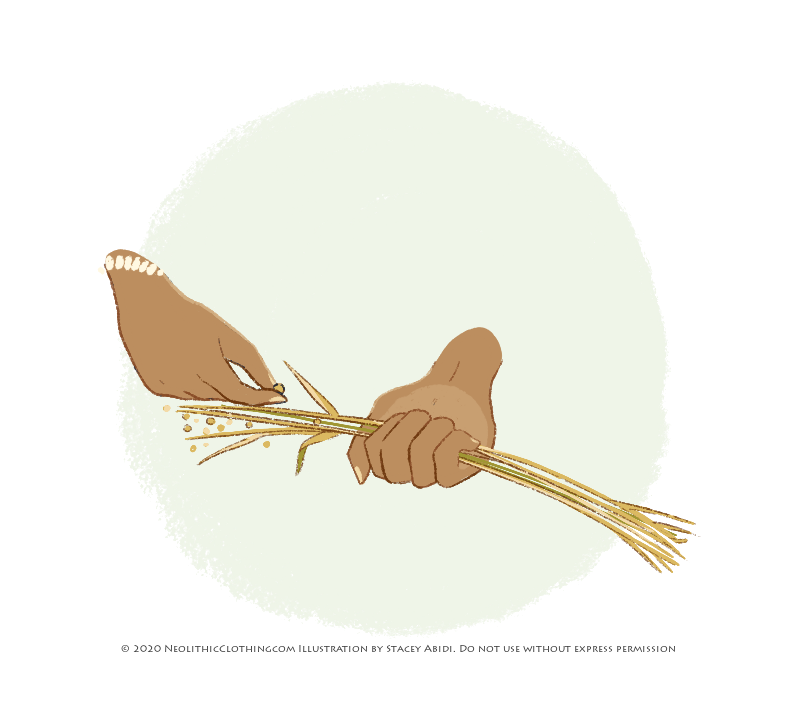

Rippling – Dried flax is passed through a comb-like object to strip the seeds. The complexity of combs, both strong enough and dense enough to be quickly effective, varied by location, and likely many different forms of “comb” were used. Without a comb, this could be performed using the hands and likely would have for small harvests.

Meneh set on a leather mat outside of her wooden longhouse, carefully holding a long polished wooden log between her legs, teeth of a comb carved into it. Grasping yet another bundle of flax from the fields, she held it by its base and carefully pulled it through the "comb" over and over, removing the seeds. The large pile of seeds and other material would be collected by her younger daughter to thresh and then winnow, but this was a separate process she need not worry about. It was possible to remove the seeds by hand, but the skin quickly became disagreeable, making the comb of great use.

A smaller bone or wooden comb could be used, but most used the larger wooden combs to increase the process's speed. After all, there were many other chores to be done. As she watched, her daughter Aneha wandered by with a large bundle of flax over her shoulder, heading to the retting pond. The smile on her face told Meneh that she and that boy, Malik, remained on agreeable terms. She had seen them talking with one another earlier as they gathered flax from the other women rippling.

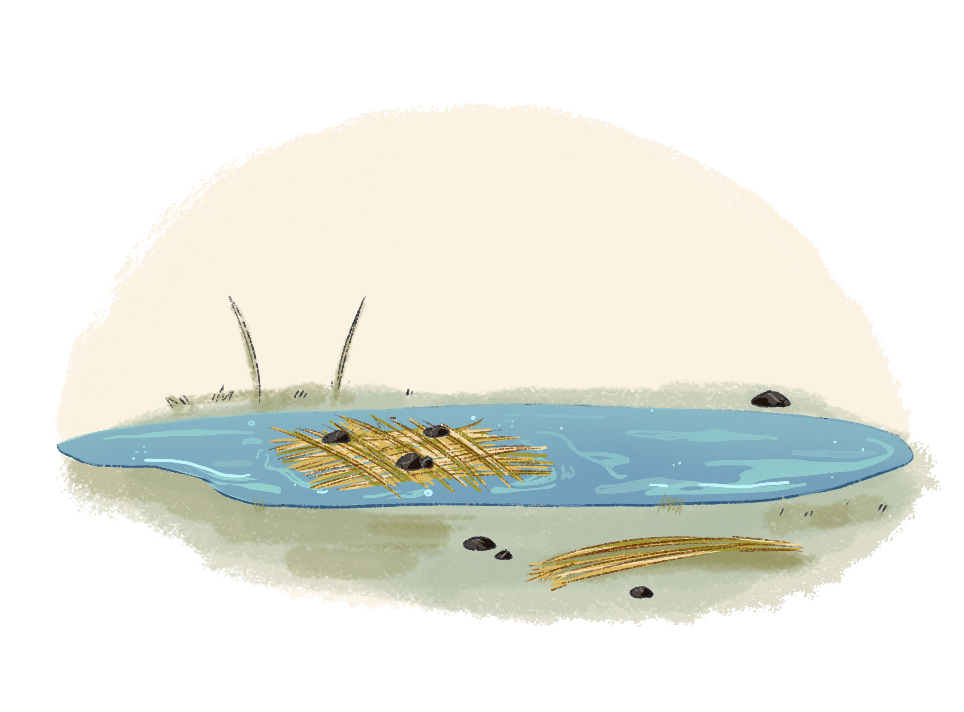

Retting – The fiber of flax is contained within the plant's stalk and must be removed. This can be done by hand by manually peeling fibers from the stalk, but this far too slow for any meaningful use. Instead, the flax's outer plant material is allowed to rot and decay, separating it from the inner fibers. This can be done in several ways, such as leaving the flax in a field to collect dew or by placing the flax in a pond, weighed down by rocks, for a week or two. During this time, the fibers will slightly degrade, but not as fast as the outer stalk. The trick is testing the flax each day and halting the process by drying the flax in the sun, once the stalk is mostly rotted, but before the precious fibers have been damaged.

About ten people stood in the retting pond arranging flax in vast, net-like structures, plants crisscrossing other plants. This maximized the water's access to the flax. Simultaneously, the crisscrossing nature of the arranged plants allowed them to all be easily held down with the fewest number of rocks. Her upper body had been painted, but this had mostly come off in the water. Luckily, her clothes were dry on the bank of the pond. There was no reason to destroy clothing with water and could repaint herself later. On her shoulders, she wore a white clay against the sun's rays. Retting ponds had a less than pleasant odor, but they were the coolest job to be had in the early warm season, aside from fishing. Some women even carried their nursing children, held against their chests using leather or woven netted satchels.

Watching the men off in the distance, attempting to remove as many stumps as they could from a new field being built, reminded her of how lucky she was for retting duty. Among the men, she could see Malik hacking away at a stump with a stone ax. Soon, they would light a fire to the stump, burning it away. Aneha dug around the water for a few moments until she found one of the large stones left from previous harvests, pulling it from the water, then placing on top of the large netted mass of flax she had just finished laying. Without the wide, flat rock, the flax would rise too far out of the water, and some of it would not correctly ret, making later processing much more laborious. She would stop in a short time and join several of the other women chanting in the retting pond's center. They would make a small offering of unleavened bread and honey to ensure the spirits of the pond helped them produce the finest quality flax. Rituals at every occasion were required to ensure the spirits did not object to their activities, causing them troubles.

Drying – The flax is allowed to dry in an open area for several days or even weeks, based on the climate. The flax needs to be flipped every few days and monitored to ensure mold does not set in and that the flax is evenly drying. Rocks can be placed over the flax to ensure it is not blown around by the wind.

Kepr leaned against a tree with a stick in his hand, thoroughly bored. Having seen ten harvests, he was hardly a man, yet. Though he knew he would become a mighty hunter, feared by all, right now, his job was to stand between the old flax fields, ensuring the winds did not blow away the drying stalks. Behind him, several men sat working to make straight wooden shafts from reasonably straight wooden sticks. Younger children would collect feathers and deliver them to Old Woman Yurn, considered by many to be the village's best fletcher. She would carefully chew sinew and fletch each arrow the men made. Between watching the retted flax dry and watching the arrows made, Kepr suspected he had the most boring job in the entire village. Off in the distance, we saw the women chanting in the retting pond, having finished laying another set of flax to ret.

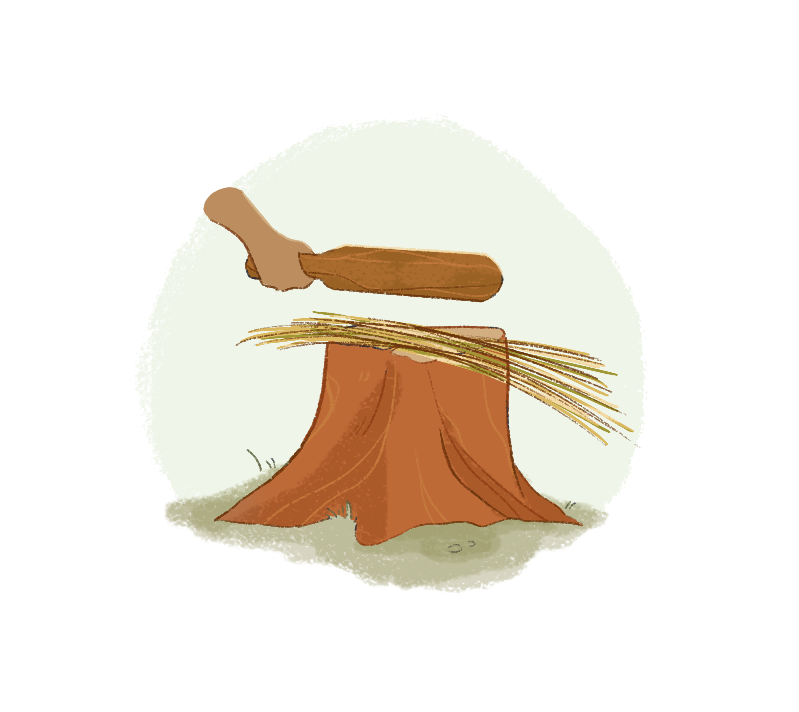

Breaking – The outer flax stalks have been rotted enough to separate from the inner fibers. However, the outer woody stalk must be broken so that it may be removed easily. The flax is placed in a bundle and beaten with wooden clubs to break the stalks, making removal of the inner bast fibers much more manageable. Wooden mallets and even hands may be used, but not rocks, as they might damage the fibers inside.

Aneha sang a song to the beat of the breaking mallet. She and four other women sat around flat-topped, split wooden logs with wooden mallets in their hands, breaking the flax fibers by literally pounding away at them. The wooden impact sounds of the mallets occurred in time, creating a beat. For a short time, a single woman would sing, and then another would take up the song with a slight variation. They laughed as each added a funny variation to her portion of the song. The men did the same thing with their tasks. Nearby, several children played with small wooden spears using a crudely made animal-like bundle of straw as a target. She smiled, knowing that one day the children would grow strong enough to do that same activity with a real animal and make their families proud. For now, she listened as the next person’s song began to the beat of the breaking mallet, thinking of how she might include Malik in her song without the other women realizing of whom she spoke.

Scutching – Flat, smoothed wooden tools, resembling a butcher’s cleaver, are struck against the flax, nearly parallel to the fibers, but at perhaps a 20-degree angle. The outer plant fiber is easily removed, leaving the long, soft bast fibers behind. Sometimes, the plant is draped over a wooden stump or log, while other times, it is held in the air. After many scutcher strikes, the fibers are left in a bundle whilst the rotted plant fiber lies on the ground.

Malik knelt on a soft leather mat with a log before him, one side of it cut flat at an angle. He draped a fresh bundle of broken flax fibers over the edge, horizontally, and began hitting them with a wooden scutching blade. The wooden tool had a flat, blade-like end instead of being a beating club. Often, old weaving swords too knicked to be used for weaving were used for this task. Each swing of the wooden blade bit into the flax, tearing of the rotted plant material from the delicate flax fibers contained within. Given the heat at the constant bits of plant fiber raining upon his legs, Malik had worn a simple leather apron hung on a leather waist cord. After he finished, he would go for a swim in the river to wash the itchy flax material away.

As he slowly rotated the bundle, beating continuously, what looked like broken, rotted straw quickly turned into a beautiful fibrous bundle of hair-like material. Something was satisfying to him about watching the final product appear before his eyes. As he looked up, he took note of Aneha sitting on a leather mat about eight lengths of a man from him, hackling her flax, the next step after one was done scutching. He had almost worked his nerve up to speak to her, and watching her flash him a smile now and then did little to weaken his resolve.

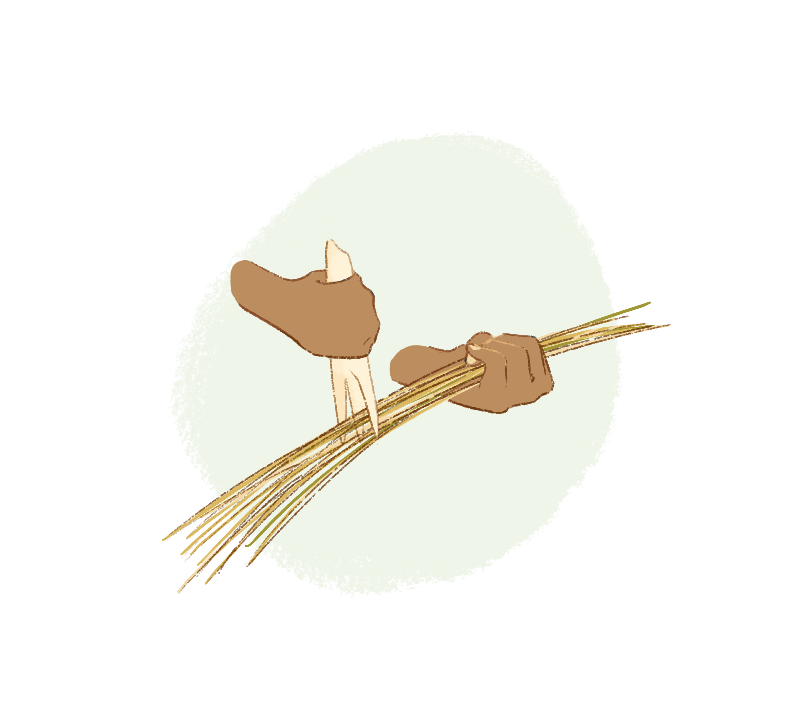

Hackling – The scutched flax can be spun into smaller threads, but ensuring uniformity of direction makes it easier to spin longer, continuous yarns. The flax is passed through a comb, similar to rippling. Longer and shorter strands can be separated. Combs could be made from wood or bone. The longest fibers, sometimes a meter in length, are used for clothing and finer quality textiles. In contrast, the shorter bits can be used for cordage or rougher use.

Aneha was not sure if she had caught Malik glancing her, though she hoped that she had. She sat on a leather mat holding long bundles of flax fiber and carefully pulling them through a thick bone comb. While technically not a required step for the flax that she now had, as it was of lesser quality and would probably be used to make small, short strings, it was a definite must for better quality flax, used to make clothing. The best quality flax would be very well hackled and made into bowstrings. Glancing up, she caught Malik peeping at her once more.

She had worn her best quality red-deer wrap and a pair of leather sandals, as well as a flax cord necklace with polished aurochs teeth. She had even gone so far as to paint her entire upper body with twice-burned bone and wood ash, yet he had said nothing, yet. She had spent much extra time that morning being painted by her younger sister, and she hoped it would pay off. If he did not come over and say something soon, she would have to take matters into her own hands. She was only but so patient of a hunter.

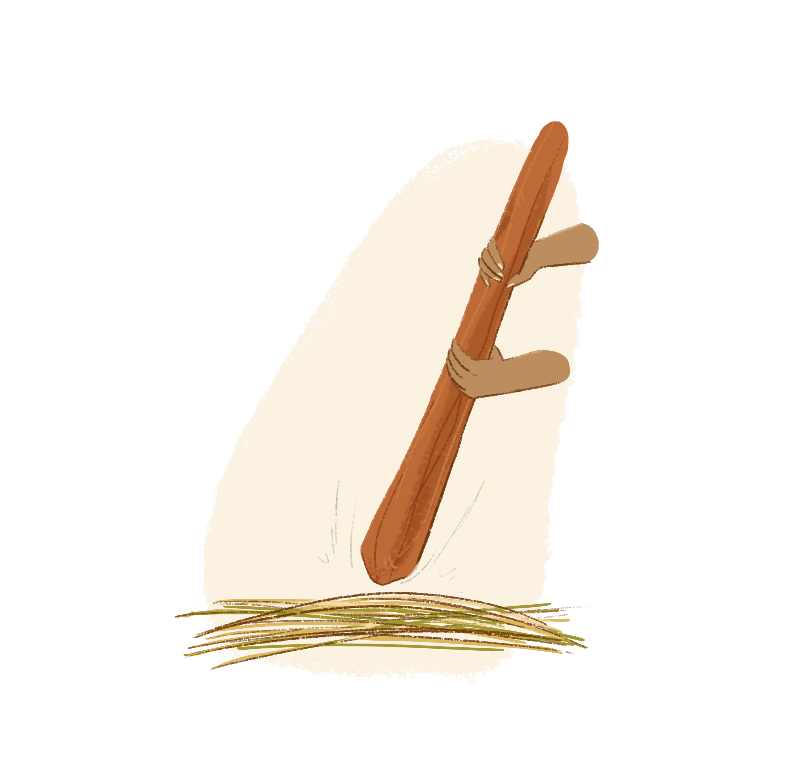

Spinning – Flax fibers can be handspun by merely pulling a little of the flax by hand, wetting your fingers first, and twisting the resulting cord. The spinner must be careful to pull flax slowly, continuously rolling the string at a constant but manageable speed. Too fast, and the string might break, being too thin. Too slow, and the string becomes too thick and does not twist well. The string may be rolled across a leg or attached to a weight that spins, called a spindle. Throughout the Neolithic, wooden spindles with a clay flywheel weight, known as a whorl, were commonplace. Some spindles had their whorls at the top and some at the bottom.

Aneha licked her fingers and tugged at the large bundle of flax fiber, pulling a little bit of the fiber into the already spun string, a continuous operation producing a continuous length of yarn. At her side, a clay whorled spindle slowly spun as her fingers flicked it. Her fingers hurt from a day spent spinning, but at least the weather had cooled. Her soft mink skin leggings and extra well-beaten doeskin breechcloth kept her lower body warm, while a doeskin shirt kept her upper body comfortable. Her feet were bare, but the temperature had not become too cold for her to wear shoes, a precious garment that took a long time to make and quickly wore out.

Licking her fingers once more, she began pulling a little bit more flax when suddenly the string broke. She dropped the flax and the string and took a deep breath. Perhaps that was enough for today. Her thoughts were interrupted by the sound of someone asking her a question, both a voice and a question she found most welcome. She was glad it had finally happened before she had been forced to do it herself.

"Aneha, eag khum de’aipku?" Malik asked her in a tentative, almost shy voice. Glancing up from her spinning, she found Malik looking down at her with a smile on his face. Wearing a pair of thick leather leggings and heavy boots, with a long leather breechcloth and a heavy belt, Malik had been out in the wilds hunting. Across his back, he carried a quiver with several well-fletched arrows and an unstrung bow attached to the side. One never left a bow strung when it was not in use. His upper body had been painted in black and white thatched patterns, obviously to please the forest spirits. Angry forest spirits were known to interfere with hunts, causing a wasted day.

Malik had just invited her to stand with him at the upcoming fertility festival during the withering season. She had decided that very morning that if he did not finally stand up and ask her to join him, she was going to do it herself. Luckily, he had asked her before she had been forced to take matters into her own hands, a much more desirable outcome in her opinion. Leaving the spindle, flax yarn, and fibers on the ground to work on later, Aneha stood with a smile. Her hands hurt anyway, and perhaps they might go for a walk and talk about things to come.

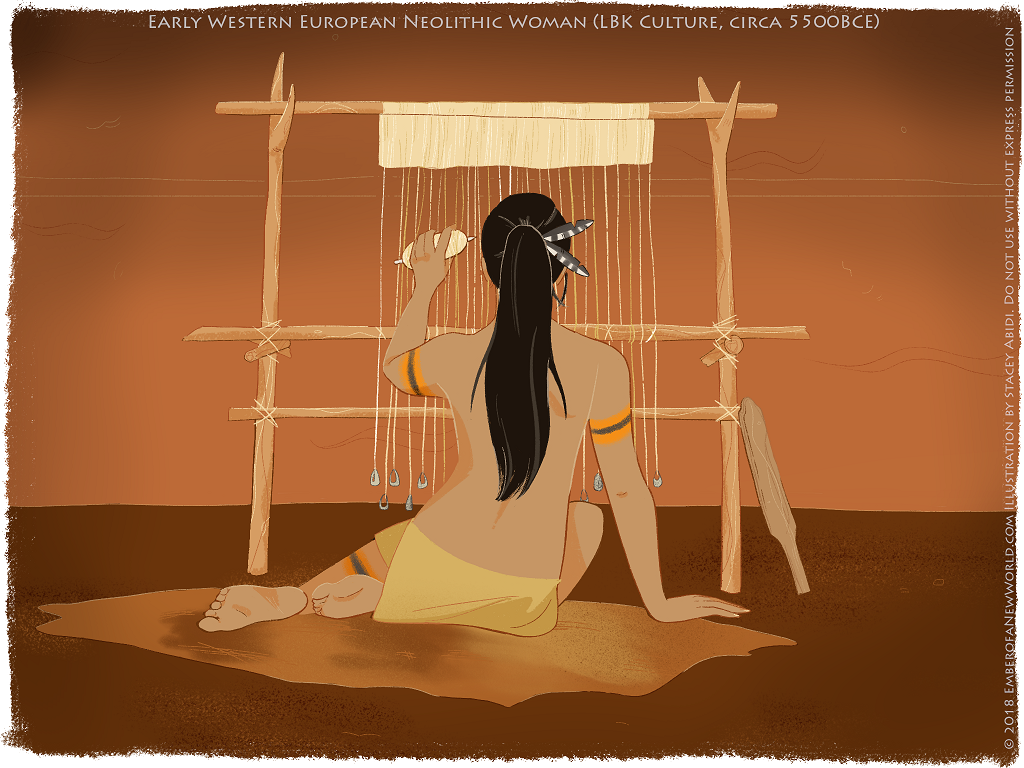

Weaving – Two-ply flax yarn can be tied to a central belt, the hanging strands producing a simple flax string skirt, while much thicker strings can be used as a bowstring, if well spun. Sometimes, however, more complex panels of cloth are required for clothing. For this, a loom is used, likely being a backstrap loom, two-beam loom, or a warp-weighted loom. It is essential to understand that clothing was not the only use for flax. String, rope, binding materials, bowstrings, and other uses of flax were just as important.

The cold season was coming as Malik and Aneha sat within their longhouse, a harvest and a half after their first walk together. While Malik carefully sewed soft fur pelts into a warm blanket, Aneha knelt before a loom working on a panel of linen. A wooden frame held strings running vertically, held taut by weighted by rocks tied at their base. Half of the string had been separated, being attached to a wooden pole she could draw back to form this opening between ever other hanging thread. Aneha pulled a flax thread through this small opening she had made, then released the wooden pole. They weighted vertical strings returned to their closed position, closing the hole she had made and opening a new one using the alternate horizontal strings. Doing this action over and over slowly formed a panel of cloth.

Aneha smiled to herself as she worked, satisfied by how things were progressing. Her stomach slightly protruded before her, a child within. Inside the family home, she had removed her shoes and her long leather shirt, exposing the magically painted markings on her stomach, which brought good luck for the coming child. A simple leather wrap would suffice within the warm longhouse. Behind her, Malik finished his soft fur pelt blanket with an exclamation. Next, he would make another bone needle and then resume work on a new wooden comb. The production of tools and materials never ceased, but neither did the cycle of life.